Postcard from Shanghai

“They are safely hidden behind a panel in the long bar at the Shanghai Club, first floor.” Then as if by an afterthought, the writer wrote, “First panel from the left side, marked with a small notch on the top panel molding.” In the dim light of the shop I read it again, “Ils sont bien cachées derrière un panneau dans le bar long du Club Shanghai, première étage. Premier panneau de la côté gauche.” The writer of the postcard had even drawn a little diagram showing the location. It was the little drawing that had caught my attention, that prompted me to read the message. The writing was small and filled the entire back side of the card. I looked at the date, July, 1916. I turned back to the front of the card and looked at the picture again, a neo-classical style building much like you’d see in New York or London. At the bottom of the card it read, “The Shanghai Club, The Bund.”

I turned the card back over and continued reading. On my fingers I felt a very fine gritty dust. It started “Chère Corinne.” I put it aside and briefly thumbed through the other cards in the packet. They all started “Chère Corinne”, or “Ma Chère Corinne.” This card, however, was the only one from Shanghai inside an envelope with an English stamp on it. One was from Hanoi but the others were mostly from Saigon, Indochine Française, a place I knew all too well. I read on, translating the French. “I have been at the Consule Générale in Shanghai three days waiting for a dispatch to take back to Saigon. Tomorrow I sail back to Haiphong, then Saigon. My battalion has orders to ship back to France next week. From Toulon we go straight to Verdun. Highest transit priority. Absolutely no leaves will be issued. I cannot come to Paris to see you. I am so sorry. I miss you. I want you. I love you.” It was signed “Henri.”

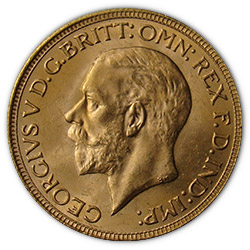

I went back to the top of the card and read more. “Chère Corinne, I post this from the British Concession in Shanghai. I don’t want to send it through the post in the French concession.”I skipped around reading different sentences. “Don’t let anyone read this. Last month in Macau I won a considerable sum at baccarat. I converted everything to English gold sovereigns, 33 in total. In wartime, paper money can be worthless. Passengers sailing for France are being thoroughly searched by customs for contraband. The same when we land in Toulon. All gold and valuables are being seized for the war effort and war bonds given in their place. Orders from Paris. As if our blood is not enough.” I paused for a moment reflecting on the bitterness of the writer’s words, understanding well the feelings behind them. I continued reading. “I tried to get a lock box in an English bank in Shanghai but regulations require permission from the French Consul. If I return to Saigon I know they’ll be confiscated. I decided to hide them here and get them after the war. I don’t know what will happen. Jean-Marie’s older brother was killed at the Somme last month. At this point the handwriting seemed to change slightly. “If something should happen to me … and I don’t come back I want you to come to Shanghai some day and get them. Inside the small satchel is a note to you. Keep this card safe. It is the only record. Know that I love you.”

I pondered this a few seconds and looked through the other cards and letters in the packet. Forty, maybe fifty in all, I guessed. I put the card back in its envelope and slipped it in the middle of the packet.

“How much are these cards?” I asked the old shopkeeper. She was at a desk poring over papers and staying warm by the heater. She raised her head and looked in my direction. She pulled a shawl around her shoulders, stood up and walked over. She lifted the packet of cards by the faded ribbon that kept them together, then thumbed through them glancing briefly at each stamp. The entire packet smelled musty and I felt a fine grainy dust when I touched the letters and cards.

“Cent francs pour tous,” she replied. One hundred francs for all.A bit much I thought. I wanted them all but not at that price. Maybe she’d lower her price tomorrow.

“Un peu trop cher pour moi, Madame, merci,” I said and turned toward to the door.

“Soixante-dix,” she said. Seventy francs. I turned around and went back to the box on the counter, pulled out two 20 franc notes and asked politely in French, “Could you accept forty francs for all?” She looked at me for a brief moment saying nothing and then smiled.

“Bon,” she said taking the money. She wrapped them in shop paper and handed them to me.

I was pleased with the purchase. I had passed the shop many times before but this was the first time I’d entered, just one of those little shops on one of those narrow streets behind the Panthéon, filled with bric-à-brac, old books and prints, small antique items, boxes of photos, letters and cards, all separated long ago from the original owners who had probably kept them till the day they died and then were disposed of by surviving family members.

I stepped out into the brisk October air. The wind had picked up. Fall had definitely arrived. It was getting dark earlier in Paris. I saw some leaves falloff the trees as I walked down the boulevard St. Michel toward Place St. André des Arts. Shoppers were bundling up in overcoats, buying things in the shops for dinner. There was a bustle of activity at the charcuterie as people were getting their last purchases for the evening. The fresh air felt good after being in the musty old shop.

I pulled the collar of my coat tight against the wind and briskly walked back to the room I rented at the back of Madame Bourlat’s apartment on the Quai des Grands Augustins. I was anxious to examine my treasure of musty old cards and letters.

On the small desk I laid out the postcards and put them in chronological order. The oldest started in 1915 with a picture of some military base in France. Most of the rest were picture postcards of Saigon and most, like the French do, were written on both sides of the back of the card over the section where the address is supposed to be and then mailed in an envelope. Some were still in their original envelope, some were not. Only two cards were actually addressed in the address section, stamped, and mailed as a card by itself. The stamps were old and faded. Indochine, République Française.

All were addressed to one woman, Corinne, Corinne Coursodon. I wondered who she was. The address was 1 Avenue Georges Mandel, Paris, 16ème. Sixteenth arrondisement, a very nice neighborhood, I thought. Outside light rain drops had started to hit my window pane. Tomorrow, if the weather was good, I’d take a walk in that quarter for the sake of curiosity, and check out the address. The next three hours I read every letter and card. From the return address they were written by Lieutenant Henri DeBerne. In my hands I was holding history, history of a world at war and the effect it had on the lives of ordinary people, a history between two lovers long ago forgotten and by now surely dead and, if not, then very old. As I read on I felt I was almost intruding into the privacy of their lives. The cards and letters were intended for only one reader and certainly not for some foreign stranger more than half a century later. It felt a little creepy but still I read on. It was getting late but I kept reading. I had only his letters that she had kept but through them and his replies to her I felt I could divine her thoughts. I felt I sensed their lives, their intimate feelings and thoughts, their hopes and fears and dreams.

Then the cards and letters stopped abruptly! The last card was a picture postcard of village of Verdun, dated October 1916, exactly fifty-four years ago to the month. Verdun, 1916, a place of over three hundred thousand battle deaths. Had DeBerne been one of them? Did he survive and return to Corinne? Was he killed at Verdun and the letters stopped, she keeping them till years later, after her death, they surfaced in a little obscure shop on the left bank, to be purchased and read by a complete stranger with no connection to either person at all. Strange, I thought. What had happened to Corinne? These were real people. There was a poignancy about these letters, a deep sense of a lingering sadness. I turned back to the postcard from Shanghai showing The Shanghai Club.

Did he really someway conceal a small satchel of gold sovereigns inside the bar’s paneling? Did he ever get back to Shanghai? If not, are the coins still there I wondered? Did someone else ever find them? Well, if they’re still where he hid them they’ve been there for fifty-four years and will probably stay there for another fifty-four years, assuming the building and the bar are still there and weren’t destroyed by Japanese bombing in WWII. This was 1970. China was not open to foreigners and in the midst of a turbulent cultural revolution. One thing was certain; no outsider was going to Shanghai. That was certain. I put the cards and letters away. I would keep them, maybe give them someday to a museum or a library or a scholar on WWI.

Shanghai, 2010. I looked in the zipper pocket of my suitcase. There folded was a photocopy of the front and back of the postcard I had bought in Paris forty years ago. The original was safe at home. I pulled out the sheet of paper. The Shanghai Club. There was no such listing. There was no address on the card, just “The Shanghai Club, The Bund”. Well, since that photo was taken early in the 20th century, Shanghai had been subjected to war, to Japanese invasion, to civil war. National governmental regimes had changed, old orders had fallen, new ones had emerged. Street names can change. An address might not mean much anyway. After all, almost a hundred years had passed since that photo had been taken. Still I had the picture of the building and much of the Bund had not changed since the thirties. Buildings like the Peace Hotel, The Bank of China, The Customs House were all intact.

I set off on a walk along Zhongshan Road starting at the Monument for People’s Heroes heading south. It was a brisk October day. Strange, I thought, just like the day in Paris when I’d bought the picture postcard, forty years ago. Walking south I passed East Beijing Road, Nanjing Road, Jiujiang Road.

Nothing, I thought, as I kept looking for a building to match the picture I had in my hand. Still Zhongshan Road and the Bund were long so there were plenty of buildings to see. Maybe it had been in a section of the Bund further South that had been torn down for construction of high rise apartments and the bar moved or destroyed and the gold sovereigns, if still there, had been lost forever. And what would I do if I found it? I couldn’t walk in with a hammer and a pry bar and start taking the bar apart. Well, I’d cross that bridge when I came to it I thought. Besides, technically speaking, the sovereigns actually belong to Henri DeBerne, not to me, though by now he’s been long in his grave even if he did survive WWI. First thing was to see if the building even existed.

At Guangdong Road I looked up. I moved closer to the street to get a better look. Six unmistakable Ionic columns peered back at me. There it was, intact and looking just like the original in the picture. The building was the same but it wasn’t the Shanghai Club anymore but a hotel and not just any hotel but the Waldorf Astoria Shanghai on the Bund. Fitting I thought. China had changed a lot in four decades. Nixon opened up China to the West in 1972 and now you can find a Starbucks in Shanghai easier than you can in Seattle. But Shanghai is not China, Shanghai is Shanghai. For all the Western luxury brand name stores on it, Nanjing Road looks more like a Fifth Avenue or a Champs Elysées than a street in a Communist country.

I entered the hotel.

“Good afternoon, sir,” the bell hop greeted me in English.

“Good afternoon,” I replied. “Could you direct me to the bar?”

“Yes sir. The long bar room is straight ahead and to the left.”

“The long bar?” I queried. I suddenly remembered that DeBerne had mentioned a long bar in his card.

“What is the long bar room?”

“Sir, the long bar is the longest bar in Asia, over 34 meters long,” he stated very proudly.

“Thank you,” I said and proceeded to the bar. Thirty-four meters I thought. That is well over a hundred feet, that’s more than a third of the length of a football field. My heart started to race. I pulled out the paper from my pocket and read the writing, “le bar long.” I had no idea what Lieutenant DeBerne had meant when I read it years ago. Now I knew. I continued reading, translating into English, ”first panel from the left.”

It was early. Few people were in the bar. Two couples were chatting at a table by the window. Two men were softly conversing in the middle of the bar. I walked over to the far left of the bar and looked at the wine list. The bartender came over.

“Could I help you, Sir”

“A glass of cabernet, please, the Australian”.

“Certainly, sir.”

The bar was magnificent, dark mahogany, with panels in the classical style of a 19th century bar. No one would even notice a small notch in such a hard dark wood. DeBerne had been smart, I thought. I reached down beneath the bar and rubbed my finger along the top molding of the panel. It was smooth to the touch. I felt again. Still nothing. My heart sank a little. I stepped back from the bar and looked down. No notch. I looked all over the molding. Nothing. Maybe he meant first panel from the left panel, not first panel on the left. I glanced at the second panel. Nothing. I checked DeBerne’s small diagram on the paper. This should be right. I stood up, slightly perplexed trying to think this through. From the postcard this definitely was the building and this certainly was the bar, the long bar. He even specifically called it that over 90 years ago, le bar long. Perhaps DeBerne meant the far left as the bartender stands, I thought. Left and right are relative terms, not like North and South. I would try that later. I didn’t want to be too obvious.

The bartender came over and brought my wine.

“I noticed you were admiring the bar, sir”, he said.

“Yes, it’s magnificent, the paneling is exquisite”

“We’re very proud of it. It is more than 34 meters in length and truly represents an appreciation of refined elegance from an era past.”

“Yes, these old bars are impressive,” I said, “true works of craftsmanship of a bygone era. It must have an interesting history behind it, being so old, …of all the people who drank here over the years, maybe some famous people? You said, it represents an appreciation of refined elegance from the past but wouldn’t it be more appropriate to say it is an enduring artifact from the past that still reflects that sense of elegance?”

“Yes, it certainly does that but I said represents because, actually, it is a recreation of the original bar which was lost, shall we say, during past contentions.”

My heart sank.

“Lost?” I said.

“Yes, lost, unfortunately. Most people think this is the original bar from 1910 when the building was built but actually it’s a reproduction of the original built to its exact specifications using archival photographs from the era”.

My heart sank lower. I took a sip of wine. I needed something stronger. I wished now that I had ordered a Beefeater’s martini.

“Whatever happened to the original bar?” I queried.

“No one knows. So much has happened in China in the last eighty years. It’s a mystery.”

“Yes, a mystery.” I repeated.

If he only knew the half of it? It’s a mystery all right, I thought to myself, but there’s more than one mystery here. I thought of Lieutenant DeBerne being in this very room almost a hundred years ago probably standing right about where I am now but at a different bar. What had been his thoughts then? In 1916 the war was going badly for France. Casualties had been not in the tens of thousands but in the hundreds. Troops were badly needed. French Army General Staff would have pulled them in from her colonies, from anywhere. With orders to the front what thoughts and feelings did he have? As a junior officer he would have known his odds of survival were low. His letters showed how deeply he cared for Corinne. They didn’t reveal much of his thoughts for the grim future he knew he would soon face. He would have had a lot on his mind in July of 1916. The gold sovereigns were probably the least of his concerns.

Questions surged through my mind. Whatever happened to DeBerne? Did he survive the war and get back to Corinne? Did he die at the front and Corinne marry someone else or marry at all? Did she keep the letters over the years unable to part with them but unable to bring herself to read them again? And what about the sovereigns? Did he survive and return to Shanghai and retrieve them or was he killed in action and the coins lost forever in the ensuing chaos in China? Did someone else find them during dismantling of the original bar? Or maybe they’re still behind the original wooden panel somewhere waiting to be found years hence? Who knows?

“It is a mystery,” I slowly repeated, speaking more to myself than to the bartender.

He nodded in agreement not really knowing what I was talking about. I drank my wine and left.

The road is the way: great narrative Nat, and I love the story. As I am immune to simplistic storylines I see the gold coins of this story represent a much greater search. One that doesn’t stop at the missing long bar;)

Well done sir!