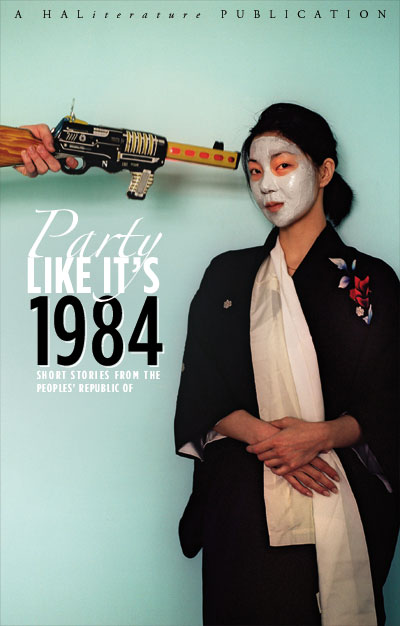

lost in the pr

by S.C.Gordon

I’ve been missing for thirteen years.

I don’t like the word ‘missing’ because it implies a sense of continuity which defeats the object of my going.

At first all I wanted to be was dead, and it was only the grey haze of confusion that clumsied my fingers and stopped them from tying a noose.

Some people think I killed myself. They come up with all sorts of reasons why. Interestingly, none of them have been anywhere near to the true reason if I’d decided to do it. It would have been easy, it really would. But I didn’t have the wherewithal to do it. Suicide requires a certain heroism, a surety that nothing will be as great as what’d already been – an arrogance that anyone will really care.

I’ve thought about going back. Of course I have. There isn’t an exile on earth who doesn’t think about it, even if what they’ve found in place of home is an Elysium. But going back would be like returning to a party after you’ve staged an elaborate and prolonged goodbye. Kisses at the door, arms squeezed in fondness, lipstick slicks on cheeks. Then you realise you’ve left behind your coat. You knock on the door and they stare at you as if you’ve come back naked. It perverts the natural order. People would have welcomed me back, though – I’m sure of it. At least within the first year. Now I’m only remembered by die-hards. A name mentioned sometimes in those ‘Best 100’ programmes, or special features on forgotten legends, unsolved cases, pub quizzes.

Shanghai welcomes the lost into her smoke-wreathed bosom like an old madame ushering a young john into her lair to choose from her loveliest. Thirteen years ago there wasn’t much here. Lujiazui was bare aside from the gleaming pink eggs of the Oriental Pearl, and the almost-finished Jin Mao which reminded me of a rattled cage until they finished it. I found myself a place to live at the top of a chokingly humid seven-floor rat-warren in Zhabei, and settled into a mottled life. Mornings when I woke, clammy and bandaged in sweat, I felt relief. Here, I was nobody again. I felt like I did waking up at home growing up, but without the ambition. Ambition is what pushed me to reach where I thought I wanted to be, and when it drained from the soles of my feet one night looking out at the barley field of fans at the Earl’s Court Arena, it forced me to disappear.

At first I thought I wasn’t alone. I believed that my misgivings were par for the course, and my reluctance to surrender to my new role just growing pains. Because I had wanted to be a famous musician since my friend and later band-mate showed me the replica Epiphone his uncle had bought at a church fete. Because it’s what everyone wants, deep down – to be a rock star.

I went through the motions. I drank the whisky, snorted the cocaine, took the groupies back to hotels. And two years after our first album went platinum, I left my girlfriend and baby daughter sleeping in a hospital ward and drove to Heathrow Airport.

The last sighting of me was in Goa in July 1997. There are websites dedicated to my disappearance. Theories are bandied about like chess pieces, even though I was officially “presumed dead” earlier this year. Being declared dead isn’t as gut-wrenching as you might think. We’re all heading there anyway.

I keep myself to myself. My Hongkou lane house is enough for me, and I scour the memories away at the end of each day before I go to sleep. I see the chalk grey of the sky, the pastel pink of the wall outside my window, and listen to the sounds that are now my native language: the tuneless violin scrape of crickets, the bleat of a Peking opera on a scratchy stereo.