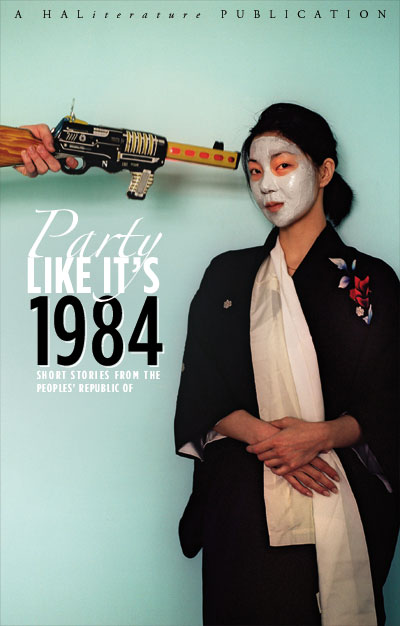

Xiao Wang’s Day at the Expo – A Field Trip Report

by S. C. Gordon

Name: Amelia Margaret Fieldman

Age: 16

Trip Report

My name is Amelia Fieldman, and I live in Gruenberg, Vermont, with my parents and my kid sister Lily. The trip co-ordinator from Swan Tours has asked me to write this report as part of the experience.

To be honest, I’m not really sure where to start. Lily is sitting beside me right now, scribbling away, but she’s much more eloquent than me, even though she’s only twelve. In any case, she sees the whole situation differently. For her it’s fiction – something she feels removed from, as if it had happened to someone else. For me it’s horribly real, and I hate it. If it was up to me we would never talk about it, but Mom and Dad wanted us to take the trip.

I didn’t want to go. The thought of finally seeing the place where it happened, after all these years of thinking about it, reminded me of the time I got trapped under a jetty at the summer house by the lake when I was eight.

By the time we got to the Expo site, we’d been in China for just over a week. We flew into Shanghai and took a train straight to Hangzhou to see where Lily was found in 1998. The co-ordinator had all the details of the place where she’d been left (a stretch of the waterfront by the West Lake, where an old woman practising tai chi had found her), and made an appointment for us to visit the orphanage where Lily had spent the first four months of her life.

I’d wanted to stay at the hotel, but Mom pulled me aside after breakfast and told me I should be supporting Lily.

“You understand it more than she does,” she hissed.

“But I never even wanted to come!”

“It’s important, Amelia,”

My parents care about the fact that I’m originally Chinese more than I do. They make me and Lily attend Mandarin school at weekends, and insist that we celebrate Chinese New Year. Bringing us back to China was their idea.

They keep our first photos in frames by their bed. As a baby, Lily was the archetypal rose-cheeked cherub with perfect oval eyes. I was thuggish and unappealing, and I know my mom and dad were disappointed when they got the photo from the agency. These days I’m short and chubby, while Lily is tall and thin. She’s beautiful. Even her birth name, Li Mei, is prettier than mine.

When I was found and taken to the police station in Shanghai, I was named Xiao Wang after the man who found me. Little king. Prince. It makes no sense since I’m a girl, but it’s ironic too, because if I’d been born a boy instead, I wouldn’t have been left there on Yaohua Lu on the morning of April 11th 1994, triple-wrapped in padded blankets with a note tucked between them. The note gave the hour and day of my birth (6.30pm, April 9th) but nothing more. Lily has a note too, but hers is much more detailed. Mom keeps it in a plastic folder, and Lily likes to look at it from time to time. She can duplicate all the Chinese characters now, and doodles them everywhere. This is a girl, it says. We cannot keep her, so please look after her. She was born on September 18th.

“My first mom wrote this,” she’ll say, and smile up at me for approval.

“Who cares?” I’ll shrug. “You’ll never meet her,”

It’s not that I want to hurt Lily, but I hate how she sees the situation as so completely positive. Sure, we’re lucky; it’s nice that we have such a great life in America, but it doesn’t make up for the fact that we were left like bags of rubbish by the side of the road.

When we reached the side of the lake in Hangzhou, Mom and Dad each took one of Lily’s hands as the co-ordinator led us to the little nook under a lion statue where the tai chi lady had found her. Lily broke away from them and stood by the statue in silence. There was some sort of aura around her right then, and I saw Mom and Dad exchange nervous glances. I know they’re thinking Is she too young for this? Lily is their pride and joy – their perfect, happy, dreamy girl. I am their first attempt – their failed attempt – at loving something that wasn’t wanted.

Lily was quiet as we walked around the grounds of her orphanage. We weren’t allowed inside but she didn’t mind. I think the sight of the children would have been too much for her.

I wish it had been the same for me. I wish my orphanage had been closed to the public, or had burned to the ground. It was the last place I wanted to visit.

Going to Yaohua Lu was bad enough. These days it’s in the middle of the Expo site, but the co-ordinator told us that back in 1994 it was a rough street in a dirty neighbourhood. Mom knew how ambivalent I was about the whole affair, so she suggested we get the visit out of the way before we looked around the Expo. I didn’t have the words or the energy to dissuade her, which is how I found myself in some sort of hell. The building where Mr. Wang found me has disappeared now, but the co-ordinator showed us where it used to be. We stood there on the sidewalk for ages, just staring at the street. After what seemed like an age, I turned to the co-ordinator.

“Can we go now?”

“Sure you don’t want to stay longer?”

“Pretty sure, yeah,”

And so we left. Lily took my hand as we walked towards the entrance to the Expo site. She obviously couldn’t tell that there was anything wrong, or that I felt like rolling under one of the people-carrier taxis that were driving by. Typical Lily, she had switched effortlessly from thinking about our adoptions to wondering what the American Pavilion would look like, or whether the Macao rabbit would be as cute as it was on the website we’d looked at. I don’t remember how the American Pavilion looked. I don’t remember if the rabbit was cute or not. All I could think of was being wrapped in three padded blankets by my mother the day after I was born, and left on the sidewalk.

I guess this isn’t really the sort of report you guys were expecting. I’m sorry. But I had to tell the truth. I wish I could say that it was a life-affirming experience. I wish I could say that it had helped, or that it had fulfilled a dream; I can’t pretend I ever wanted to see the place where I was left. Besides, it’s changed now. What used to be a muddy street in a ramshackle district is now in the center of something bigger. What used to be a statistic of a discarded generation – an abandoned baby girl – is now part of a different world. You can’t go back. You just can’t.