Hard Seat from Shenzhen to Shenyang Chapter 1

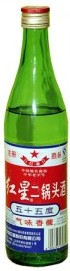

Er-Guo-Deas

She woke up to the smell of chicken bones and fangbian mian. She tried to sit up.

Her head hit the thick metal springs. She had been sleeping underneath the seat.

The night before, she had met an American boy celebrating the end of his teaching tenure and the beginning of his winter travels. He’d been gifted two bottles of baijiu from the school. They finished the first one together.

She remembered being very sick, and declining his offer to share a joint in the squat toilet.

He had left the train at one of the small dark stations in the early hours.

She had tried to sleep in the carriage aisle; but the rice trolley couldn’t get by, so the other passengers rolled her under the seat, with the chicken bones and discarded fangbian buckets.

***

She rolled out from beneath the seat.

She sat up in the aisle.

“Good afternoon,” said a portly grandmother, leaning forward to unstick a candy wrapper from the girl’s forehead.

“Are we nearly there yet?” said the girl.

“Shenyang? Maybe 36 hours to go,” said the grandmother, cheerful.

The girl closed her eyes.

“Get up. Up. He’s coming again,” said the grandmother, prodding her. The trolley was on its way back through the train.

All that was left was cola, and dried white rice in sagging polystyrene boxes. She bought some and ate with concentration, washing down every desiccated mouthful with a measured swig of flat cola.

She tried not to wretch.

Someone had taken the seat she’d had, before the boy and the baijiu. When she’d finished eating, she lay down in the aisle and rolled herself back under the seats.

She stared at the springs above her. She wanted to remember what they’d talked about last night.

Some shit about the weightless anonymity of travelling alone: They could do anything; they would never see anyone on this train ever again; they would never tell anyone what had happened.

They talked about the trips they’d made before. He’d been to see the wall and the warriors.

They started an argument about the traveller and the tourist. He’d booked a halfway decent hotel in Shenyang. She said that was cheating. He got pissed off and said he was a real traveller, a gypsy snail, carrying his home on his back.

Not that he needed any of it. He could live on his wits.

She had giggled at his sincerity, which was cruel, but it was four in the morning and she was drunk.

Then the train stopped at Xia- something, somewhere.

“I’ll prove it,” he had said, and he got off the train.

***

The girl opened her eyes again. She still felt sick, she decided.

Hair of the dog might be a good idea. She would look for his backpack.

It was where they’d left it after he’d looked out the first bottle of baijiu. A burly passenger helped her to take it down, “Your friend’s,” he said with a stiff nod.

She opened it up in the corridor between the carriages, and sifted through the upper layers of sweaters and socks. The second bottle of baijiu was nestled in the dirty laundry.

She sat on the pack, unscrewed the bottle and sipped.

This wasn’t a normal hangover, she thought. She felt lucid.

She sipped some more, and watched the fields blur past.

She couldn’t remember why he’d wanted to go to Shenyang anyway. Was it just the impressive distance from Shenzhen?

She sipped again and sifted her memories.

She found that the baijiu made her thoughts fall in a rhythm she couldn’t quite follow.

Why had she thought it was a good idea to go to Shenyang? She didn’t know what the fuck she’d find there.

She drank more deeply.

The grandmother passed through on her way to the squat. She squinted at the half empty bottle, made a sleeping gesture and pointed back beneath the seats in the carriage.

The girl shook her head and took another sip.

By the time the grandmother came back, there was an inch of baijiu left.

The girl felt a funny sensation as the old lady wobbled by, and wondered if she was going to be sick again.

Then something fell into place; she understood that the train was about to stop.

The girl put a hand on the grandmother’s wrist as she steadied herself against the wall. She gestured that the baijiu was for the grandmother to finish, and stood up with the clarity of purpose. She zipped up the pack.

“Not Shenyang,” said the grandmother. “Wait a little. Maybe 30 hours.”

“I’ve arrived,” said the girl.

The train stopped.

She turned to fumble with the heavy metal handle.

The door swung open.

She threw the boy’s bag to the ground.

She clambered down the steps.

The door swung shut.

As the train moved off, the grandmother waved her farewell.

Swaying in the early evening breeze, the girl watched the train slip away.

This is part of a ongoing collaboration between HAL writers. It continues here.