The Descendants

Cold night air bit at her rosy cheeks. The stairway to the train was a surging swamp of bodies. Kuan surrendered to the pull of the crowd, allowed herself to be lifted upward and carried like a rag doll to the platform. She let the tension and myopia of work seep from her muscles, and dreamed of home.

Just through the doors and they groaned shut, ripping jackets and dividing families. There was always the next train, she thought. In six hours. Maglevs heading west to Tibet ran on a sparse schedule, so once every six hours wasn’t bad for New Year’s traffic. She pulled the hood of her sweatshirt tight and closed her eyes, losing herself in the grind of metal on the cheap headphones.

Kuan was traveling alone. She hated crowds, which was unfortunate for a factory worker living in the Shanghai sprawl. This was the only time of year when she could return to the relative open space of Tibet, to the mystical clouds of her childhood.

Her parents were transplants from Hong Kong, engineers who had heeded the call of the Great Floating Lama and her grand scheme to raise towers in the sky. They too looked forward to the New Year as much as Kuan. They loved their only daughter even more than the enchanted elevators they had spun for the Lama.

Most of all, however, Kuan was dreaming of Chong Dak, her shining lover in the clouds, the ingenious osteomancer who conjured life from nothing. It wouldn’t be long now, she thought, before he would graduate and his father would let him marry her. On that day she’d spit on the factory door and fly home on the train for the last time, forever to be embraced in the arms of his wispy world, all full of incantations and wonder.

With a shuddering whine the fusion engine of the train cracked to life. High-pitched English erupted from the speakers. “Welcome to take my maglev!” Then safety instructions in Mandarin. The neon lights flicked out. Still standing and pressed against other expectant travelers, Kuan tried to hold the image of Dak in her mind as sleep claimed her.

But it didn’t work out. Instead of dreaming of Chong Dak’s embrace on breathtaking mountain peaks, she found herself under the bright fluorescents of the factory floor, sorting through row after row of hard plastic skulls, marching by her station on the rubber belt. Woops, that one has too much black paint in the sockets. There’s a hole in that one, and that one’s missing the gold tooth. Pull the defects off, toss ‘em in the bucket for local sale.

She knew she was dreaming, but she was so meta-exhausted that she couldn’t summon the energy to wake up and try again. Fine, back at work. She would let her mind drop the subject in its own good time.

What the hell do people do with realistic plastic skulls? She imagined a group of foreigners on a bachelor party, guzzling from a keg and throwing her best work at fishnetted prostitutes who smacked them into the night with aluminum bats. Home run! She wondered why she had bothered learning how to read.

A sudden burning sting on her cheek.

“Shit!” she screamed, pulling her face back from a snoring man’s styrofoam bowl of chemical noodles. The dull glow of the floor lights gave the old man a demonic pallor. Kuan groaned and dragged herself upright.

Damn. Have to pee, she thought.

She battled her way to the end of the car, watching faces flash in front of her as lights outside flew past. It had only been an hour, and already the odor of irritated bodies was making her nose wrinkle.

Thankfully the toilet was open. Squatting over the trough, she fumbled through her bag. She fingered a small box with a trigger guard sticking out. Several strips of wiring, and something that felt like a fork with buttons on it. The dream of work had reminded Kuan that she had homework for the New Year’s vacation. Her boss had tasked her with perfecting some components for the sonic shotguns that the Shanghai riot police used, along with some other less-than-legal devices that were designed with the intention of knocking out said sonic weapons.

At least her upbringing and education had got her something. These little side jobs paid more than a month’s salary. As long as her boss didn’t get caught.

Thirteen, she thought. That’s how old I was when I met Dak. Smarter than average kids, with so much to choose from. Engineering projects, ethereal forces of the universe, floating architecture.

But it turned out that I’d make more money sorting plastic skulls, she mused. Of course Dak was a brilliant osteomancer, his career path shining before him on the rooftop of the world.

“Great-great-grandmother? Is that you?” Kuan almost fell backwards with her pants down. Where did that voice come from? It sounded like it was inside the small room.

“Up here,” the voice continued.

Kuan stood up and squinted in the weak light. The mechanical towel dispenser was flailing its little metal arms.

“It is you! Please, I have something to say.” The arms stretched out in a supplicating gesture.

Kuan kicked the flushing valve and pushed through the door back into the crush of half-sleeping passengers.

I can’t be that tired, she thought. Did I do any drugs last weekend? No, not since Christmas on the Bund. What was wrong with that thing? Towel dispensers are supposed to hand you towels, not engage you in conversation. Bah, she shrugged it off, slinking into a corner and closing her eyes again.

* * *

A blaze of mountain sunlight woke her to the relentless crunch of the music still on repeat. She pulled the headphones off and the noise seemed to continue, but it was only the loud hiss of the oxygen pumps. The train was crossing the pass, soon to begin the long descent into Lhasa.

She took a gulp from her flask of tea and swished it around in her mouth, trying to erase the sour taste. She felt a sudden drop. Her ears popped and the windows went black.

“Where the hell are we going?” she asked, the flickering neon struggling with the dark.

“Train syncs up with the Lhasa Metro now. Goin’ straight through the mountain,” someone said from across the car.

“Huh.” Kuan imagined Chong Dak summoning up one his odd armies of bondsmen to toil endlessly through the darkness, to tunnel through the solid Earth.

The whine of the engine began to slow.

“That was fast-“

In a split second Kuan was wrenched through the air. She smashed into a bulkhead as the train stopped in a tremendous shuddering of metal. Black.

Flickering white dots played across her vision. Groans from other passengers. She had the wind knocked out of her. She lay gasping for a few minutes. She heard the sound of medical robots cutting through the doors, and the lights came back on.

“Please direct us to those most in need around you,” they asked politely. Kuan got up and walked past them in a daze.

Outside on the tracks there were spotlights and rescue crews of robots and people. That was fast.

On the ground a strip of glowing arrows pointed the way to a freight elevator. Mobs of people shuffled along like sleepy yaks while the injured were shuttled along in stretchers by thin, mechanical hands.

The elevator was at the end of the lighted section, where the front of the train had jackknifed into some unseen obstruction. The doors closed just as she reached them. Something caught her eye in the dark, further down the tunnel.

Movement. Thin and white, reflecting the light. It came closer, slow and deliberate. None of the people around her seemed to notice. The form took shape. It looks like a person, she thought.

Nope. Definitely not a person. There was no head. It had to be a bone drudge, one of her osteomancer’s creations.

The figure stopped a few meters from her, clearly visible. Still no one seemed to care. Then the acrid smell of burnt hair hit her nostrils. That smoky, arcane scent of the studio, where he sparked fires to marrow and animated the mismatched skeletons of animals and forgotten humans. Home at last! How exciting.

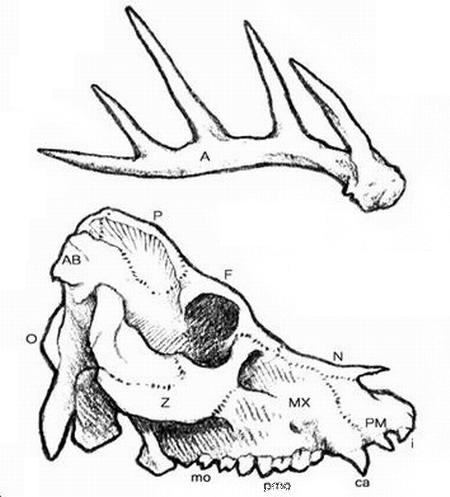

The figure gestured to her with his oversized left arm, which appeared to be a mastodon femur. There were horse hooves lashed tightly to the end in a web of stretched leather. It stumbled with the shift in weight, then stopped. It was as if it had just been summoned into being, and didn’t know it’s own body.

Kuan stepped towards the bone drudge.

She was there the first time her lover had evoked a clattering beast of bone, his first drudge. They had snuck into his father’s musty studio at night. He found a pile of discarded and unsorted bones in a crate and dragged them to the touchstone in the center of the room. He cut thin grooves in the bones with a laser knife, then torched the marrow into an eerie glow. That acrid smoke.

Dak had tried to act brave, his adolescent voice cracking as he muttered the incantations, scientific names of dead animals in Latin. There was a sheen of sweat on his forehead reflecting the candlelight.

The glow increased, and the smoldering pile of bones had assembled itself into some kind of dog-snake…something. Whatever it was, she was so impressed that she had kissed him on the lips and he fell in shock to the floor, nearly torching his own arm with the laser.

A sound like someone chewing on broken glass broke her from the reverie. “Hrgh, yoooouuuuu…aaaaarrreeee…”

Kuan jumped. Was it speaking? How? Drudges can’t speak.

Little shards of bone splintered into the air from the rib cage, where a bound rock was vibrating against a human finger bone. The smaller right arm pulled and prodded at its chest, trying to adjust something. After a few more awful bouts of rasping, the sounds became a voice. Or closer to a voice.

“Ahem. Great-great-grandmother. I have something to say.”

Kuan frowned, looking back at the crowd of passengers paying her no mind as they pushed their way into the elevator. “You. The towel dispenser? How can you be out here haunting drudges? How did you know where-”

“I’m not a towel dispenser, and I’m not a drudge either. I’m your descendant, and I am here to help you.” The small bony hand pulled a candle from a bag, which seemed to light of its own accord.

“Follow me, I’ll take you home.” The drudge started off down the black tunnel. Kuan shrugged and followed.

The drudge walked in silence ahead of her. It was a long time before Kuan realized that several more drudges were shuffling along behind them. The burnt hair was joined by the greasy odor of their yak butter candles.

“Great-great-grandmother,” they rasped in unison.

It dawned on Kuan that maybe this was something Chong Dak had cooked up, a welcome home joke. Except he wasn’t really one to joke when it came to his art.

“You can’t marry him,” the drudge said. “You’ll ruin us. I mean, we are ruined. But you can help us.”

She tripped on a rock and fell into the drudge. The bones were warm. She pushed back and stood scowling at it.

Another voice crackled behind her. “We know you. You are rational.”

“Please understand,” another said. “Save us from the shame. Find someone else in Shanghai.”

Kuan pulled back her hood and turned to see a circle of drudges standing around her, looming like angry fairy book monsters.

“I don’t know what you’re up to, but I’ll have Chong Dak turn you all into lawn chairs if you keep it up.” Her voice quavered. A cool wind whistled down the tunnel.

Mastodon arm moved closer to her, and pointed at the wall where a square panel glowed a soft blue. “We’ve reached an elevator. It will take you up to your home. We mean you no harm. We are not bone drudges, or towel dispensers. We are time travelers. We just can’t come back all the way. We have to…inhabit something.”

The smaller arm reached out to her. There was something shiny in its fingers. She hesitated, then took it. A gold locket, twinkling in the flicker of the yak butter candles.

“In our time, the art of osteomancy is an abomination, as is any conjuring vocation. We are outcasts! Beggars, shivering in our giant stone mansions with no electricity, or even servants.”

Kuan tugged nervously at the drawstring of her sweatshirt, turning the locket over in her fingers. “How do beggars travel back in time?”

The drudge shrunk back a step. “I- our family has not changed since your time. All we know is the sorcery that your husband began. That is why we are so cursed! At least this dark knowledge has allowed us a final effort to put things right.”

Another drudged lunged at her from behind. Talons closed around her wrist and pulled her backwards. She screamed, and tried to yank free. “We’d rather not be than fall to such shame,” it growled at her. “Erase us! Make us something else!”

With a heavy crunch the big arm of the leader separated the raptor claw from its grip on Kuan. “Let her go! We mean her no harm.”

She scrambled away from them, and ran for the wall. She slammed her hand to the blue light, and the wall slid open. The door shut and the internal lights came on, but she could still hear the voice outside.

“Please! Think about us, think about your children!”

Kuan punched in a number on the pad, and she felt the elevator rise with gaining speed. The walls faded into translucence and she winced in the sun. Only the floor seemed solid, the mountains and clouds stretched out around her as she rocketed skyward. Nausea came, this was the worst part. She’d always pretended that she loved it for her parents, but secretly she hated heights.

She focused on the locket. She ran her fingernail along the edge, chipping her black polish. The locket creaked open. It was a tiny hologram of an old woman smiling. Hard to be sure, but it definitely looked like Kuan.

* * *

Kuan watched the grime and dust of the tunnel flow in rivulets down the shower drain. Sometime in the last year her mother had put a huge window in the wall, and she was trying not to glance out at the snowy peaks. As a child she’d gotten used to the constant swaying feeling of life in the floating tenement city, but so much time on solid ground had spoiled her.

My children, she thought. Ungrateful bastards! Fine, we just won’t have kids.

“Kuan, I’ve just heard some bad news,” her mother said, shoving a towel through the door.

“Mom! Let me finish my shower.” She grabbed the towel and dabbed her face.

“It’s Dak’s father. He just passed away. Dak is performing the sky burial right now, out at Drigung Til, if you want to meet him.” Her mother looked down at the floor with a frown, but it wasn’t very convincing.

“Of course, I suppose this means the two of you could marry now, even though Chong Dak isn’t out of the academy yet. If you leave now you can probably still catch a bus out to the pass.” Her mother smiled and closed the shower door.

Kuan’s parents would like nothing more than to have a daughter married into such a noble family. Well, that’s something anyway, she thought. Who wouldn’t listen to their parents over a bunch of rogue skeletons from some whacked-out theoretical future?

Kuan dressed quickly and grabbed her metallic purple parka. She hoped it would cheer him up. Dak always made fun of her for it, claiming they looked like the ultimate odd-couple when she wore it; him in his austere traditional Tibetan wool, her looking like a circuit party victim.

The mountain air was thin and cold. After the spine-jarring bus ride, it was a welcome change. She made her way up the trail, passing little earthen houses and wandering children. Prayer flags flapping in the wind. Over the rise she saw vultures circling.

Chong Dak was wearing an old herdsman’s coat and a red hair tie. His features were sharp and weathered, eyes intense and frozen. He stared upward at his father’s body on the ledge, ensconced in sticks and juniper branches. The birds were landing, soon to pull away his now useless flesh.

He turned and smiled. “Kuan, you’re here.”

He glanced at her parka and laughed. They embraced, she ran her fingers along his face. “You’re okay?”

“Of course. He was ready. It’s just a shame he wouldn’t let me keep the bones. Humility, you know.” He gestured at the vultures above. “Didn’t want to deprive nature its due.”

Dak pulled his rough coat close around them. “When he was a child, he was a horseman, from a simple family. These were his father’s clothes. He never wanted me to forget that. He sought out osteomancy and made a kingdom of it for us.”

He stared into her eyes and cocked his head. “What’s wrong?”

“Our kids. They’re haunting me, and I don’t think they’re going to stop.”

Kuan recounted her adventure in the tunnel. They rode together back down the trail on shaggy Nangchen horses that snorted the thin air into their ample lungs.

“Time travelers? That’s fantasy nonsense,” he said, snapping at the reins. “It must be some kind of trick.”

“It may be nonsense now, but who knows what you’ll achieve in the future.” Kuan decided not to show him the locket just yet. No need for him to start thinking of her as an old woman.

Suddenly the horses stopped. They bucked nervously, whinnying.

Something was fast approaching them from lower on the trail. Dust rose around it in a cloud. It looked like a yak, but-

“Great-great-grandmother,” the skeleton declared, as it crashed into Chong Dak’s horse, toppling him.

The headless yak drudge pulled up its forelegs, creaking under patches of dried skin. Dak rolled away before the hooves could crush him, and jumped up on Kuan’s horse.

“Go!” he yelled, digging his heels in and holding Kuan tight. The drudge turned and stampeded after them. Several children stared from the trailside in awe.

“What on Earth do you use those for?” Kuan cried.

“They make good guard dogs,” Dak muttered.

They raced down through the valley and out on to the open plain. Somewhere on a hillside a sad song echoed from a farmer’s flute. Each time they tried to break in a new direction, the drudge would surge ahead, corralling them out into the wasteland.

Eventually the skeleton faltered, pieces coming off, but still it followed. The sun was sharp and bright overhead.

Chong Dak looked back and saw it stumble. “Slow down, let’s give this old boy a rest.” The Nangchen was relieved, spittle dripping from its wheezing mouth.

“Look,” Kuan said, “It stopped.” The bones were in a shifting pile. They dismounted and walked next to the horse, still heading away from the yak drudge.

“They’re really not made to run this far,” Dak said apologetically. “They actually do a great job of guarding one spot, I swear.” Kuan smiled.

There was a scratching sound from the dry, cracked earth ahead of them. The horse stopped. They pulled, but he refused to go further.

A huge fissure ripped the ground under them, and then everything dropped. They fell into a cavern, horse and all. The Nangchen let out a piercing cry when it hit the bottom, Kuan and Dak landing nearby in a heap. They stood up coughing, trying to squint through the weak rays of sunlight swimming in the dust. A flow of dirt was sliding over the edge of the hole like the sand of an hourglass. The horse moaned.

“Oh, no, he’s broken something,” Dak said. He petted the horse’s neck, trying to soothe its muscle spasms.

“They’re in here!” Kuan yelled, backing toward Dak, away from the shadows. A circle of bone drudges closed on them.

The mastodon femur clubbed Dak to the ground. Kuan rushed to protect him, but something wound its way around her throat. The stink of old flesh, a rope of dried tendons pulled by a drudge. She tried to pry if off, but was dragged backwards like a dog on a leash.

“We will stop this if you can’t,” the drudge leader said calmly. He stood over her prone lover.

Kuan could feel her consciousness slipping, her vision blurring. The drudge had her neck tight, no way to pull out of his grasp. She let go of the tendon rope.

“Cut his neck, end our worthless line!” The descendents crouched around Dak with pale knives.

Her bag was tangled around her leg, but she was able to pull it open. Fingers flailing for the right shape. Got it. The trigger guard.

The concussion wave from the sonic burst launched her across the cavern, and her vision went black.

It was so quiet. Not even a ringing in her ears. She woke to more dust. She coughed hard. Silent. Her vision returned. The cavern was a mess of bone and leather. Her own body felt like one giant bruise. At least living bone didn’t break so easily.

Kuan crawled toward Dak as fast as she could move. She breathed a sigh of relief. He was sitting up, holding his head. His mouth opened in a yell when he saw her, but no sound.

She reached her hand to hear ear…blood. Ah, that explains it. There must be a doctor in Shanghai that can pop in some new eardrums. They huddled together in the dim light, their happiness staving off the throbbing pain in their heads.

Kuan reached out and picked up a piece of splintered bone. She was sad in a way, that something as flat and boring as a sonic shotgun could erase such magic.

* * *

Chong Dak snored next to her. Of course she couldn’t hear it, but she could see the other passengers glaring at him. His head was bandaged in colorful Tibetan scarves. There were still dark patches of blood near his ears. She wondered if anyone in his family had ever been this far from home.

Convincing him to leave with her had been impossible at first, but she won the argument when he saw the locket and finally came to realize that the drudges actually had been who they claimed to be, that they would be back in some other form.

Kuan sighed. Back to the endless march of plastic skulls. Chong Dak was going to hate Shanghai. She would probably be able to get him a job at the factory. The boss would owe it to her, after the successful field test of his side project.

But Dak would have to find some new way to use his talents. There was no way she was going to let her children grow up feeling entitled. No way. Let them start on the assembly line like everybody else. She was going to teach them science and make sure they only got dessert on special occasions. No sleeping in on the weekend, no fancy cars or flashy clothing.

She smiled, imagining her husband throwing skulls at her across the rubber belt.

Spires in the sky, oh my oh my…

I found the piece a bit jumpy for my taste, but there are some wonderfully developed images: the drudges, the demonic noodle eater on the train aloof in his noodle sloshing and the feeling of a sonic shotgun.

This is a world I hope to know more about in the future.